Episode 7: Anaphylaxis Part I, Refine your Approach

Today, we’ve got not one, but two guest experts to help Dr. Rajiv Thavanathan tackle all things Anaphylaxis! Dr. Graham Wilson is an FRCPC EM resident at The Ottawa Hospital (TOH), who tackled this topic in-detail in his Grand Rounds presentation last year. Joining him is Dr. Derek Lanoue, an incoming McGill Allergy and Immunology Fellow. Let’s dive right in to Part 1 of 2 on this nutty topic!

What is the Diagnostic Criteria of Anaphylaxis?

It’s very difficult to summarize “anaphylaxis” in one definition. To tackle this problem, in 2005, The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network came out with the criteria most ED docs probably teach on shift today.

2005 NIAID and FAAN Anaphylaxis Criteria

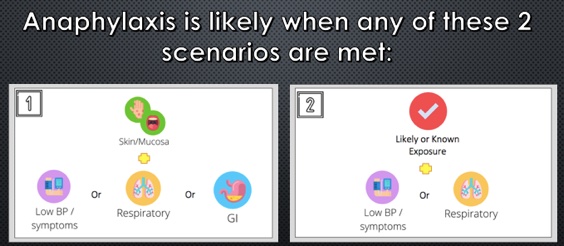

- Anaphylaxis is highly likely if:

- Unknown exposure with acute onset of illness

- AND Skin OR mucosal changes

- AND Respiratory compromise OR reduced blood pressure

- Likely antigen:

- Two or more organ system involvement: Skin, mucosa, respiratory system, cardiovascular changes, or persistent GI symptoms

- Known allergen:

- Reduction in blood pressure

- Unknown exposure with acute onset of illness

This definition was prospectively validated with a sensitivity 95%, though we aren’t applying it as effectively as it should. A study in the USA by Russell et al. in 2013, and more recently out of the Childrens Hospital of Eastern Ontario in 2020 show that:

- We are underdiagnosing anaphylaxis upwards of 50% of the time

- Why? Definitions are too restrictive.

- “What do persistent GI symptoms even mean?” “Is one episode of emesis enough?”

Things changed for the better in 2020, when the World Allergy Organization tried to simplify things for practitioners.

2020 World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Criteria

- Anaphylaxis is highly likely if:

- Unknown exposure with an acute onset of illness

- Skin findings, and one other organ system

- Likely or known antigen

- Respiratory AND/OR cardiovascular compromise

- Unknown exposure with an acute onset of illness

How can we improve allergy/immunology referrals?

The purpose of our anaphylaxis criteria is to maximize sensitivity to not miss this life-threatening diagnosis, and to administer the antidote, epinephrine, as soon as possible. This poses the question though – what might this approach be sacrificing, from the perspective of the consultant who will see this patient in follow up?

Dr. Lanoue brings up a great point – it’s all in the objective evidence. Did you hear wheezing when you examined them? Do they have hives you can photograph (with consent)? Have they vomited? How many times? Did they have an episode of diarrhea in the ED?

“Okay, but what about tryptase?”

Triptase is an intermediate in anaphylaxis, which causes activation of the compliment system, and mast cell degranulation. This test takes ages to come back, so often it won’t get drawn as part of the work-up for anaphylaxis – some centres won’t have it?

Dr. Lanoue recommends the following from the allergists’ perspective:

- For the vast majority, get the level.

- It doesn’t help in the acute setting; it won’t help you decide whether to give epinephrine or not.

- It can be very useful, however, for the consultant allergist.

- The level peaks within an hour, and is back to normal within 4-6h. Any patient who presents within this time period from onset may have benefit.

Tryptase levels are useful in the patient where there is an unclear trigger. We know there will be many patients who are tryptase negative, despite being in anaphylaxis. The reverse is also true. In the setting of an unknown trigger, especially when there is diagnostic uncertainty, this may provide another objective piece of evidence for your consultants. Anaphylaxis is not the only diagnosis that is indicated by an elevated tryptase (e.g. mast cell degranulation syndrome).

What is the dosing of epinephrine for anaphylaxis?

- Epinephrine: 0.01mg/kg, up to a max of 0.5mg.

- Anyone below 25kg: 0.15mg Epinephrine auto-injector (e.g. Epipen Jr).

- Anyone above 25kg: 0.3mg Epinephrine auto-injector (e.g. Epipen).

- We can provide weight-based dosing in the hospital setting, and encourage listeners to do the same to get the most benefit from epinephrine as possible.

- No established RCT on dosing. Even the 0.01 mg/kg is opinion-based, and based on data on normal adults, not those having anaphylaxis, using measured levels of epinephrine in the blood level.

What is the ideal site of administration for anaphylaxis?

Dr. Estelle Simons is a (Canadian!) prolific researcher in the field of Allergy and anaphylaxis and has served as president of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI). She performed a study measuring peak epinephrine concentrations in healthy, adult volunteers in the deltoid muscle vs the lateral thigh, showing a higher level in the lateral thigh. This is likely due to a higher concentration of vasculature. More of her work showed a difference in the rates of absorption in intramuscular vs subcutaneous administration of epinephrine. Other researchers have demonstrated that the thinner subcutaneous tissue over the lateral thigh allows for more consistent penetration to the muscle.

In summary, use the lateral thigh and use the intramuscular route.

Another huge take away point by both guest speakers is that IV bolus delivery of epinephrine for the treatment of anaphylaxis is associated with increased adverse outcomes compared to both IM and SC.

Use of steroids and antihistamines

These are a very controversial topics, with lots of dogma surrounding the medications we use. In theory, steroids work in two ways. First, it decreases the symptom burden in the acute phase of anaphylaxis. Second, it helps to prevent the concerning, though ever-elusive unicorn that is the biphasic reaction.

In the acute phase, the evidence from steroids came from children with asthma and croup, looking at preventing hospital admissions, and relapse rates. Maximum steroid serum concentrations occur within 1-2 hours, which means that it’s highly unlikely to prevent death from anaphylaxis. We know that death from anaphylaxis occurs within 30 minutes of trigger exposure, which is well outside of the effective window for the steroid.

What we do know is that epinephrine is the first-line intervention for anaphylaxis, with the greatest mortality benefit. Despite, in a cohort study of close to 2000 children diagnosed with anaphylaxis, less than 25% received epinephrine, with almost 50% received steroids.

So what about the biphasic reaction? The biphasic reaction is recurrent anaphylaxis, after complete resolution of symptoms, without re-exposure, within 72 hours of the initial anaphylactic event.

A few facts about the biphasic reaction:

- Rates range from 4-5% of anaphylaxis cases using the above definition.

- Most present in a clinically similar manner to the first episode.

- Only 20% of these patients required additional therapy on top of what they originally received.

- Steroids in the ED first gained favor in 2007 when a single-centre prospective study showed decreased biphasic reactions with use of steroids.

- Since that time, several systematic reviews argue against preventative association of biphasic reactions, and one study went so-far as to recommend against the routine use of steroids for anaphylaxis.

- Further, there have been no reported cases of mortality due to biphasic anaphylaxis as per the 2020 AAAAI Practice Parameters

- Clinical Features of biphasic anaphylaxis (low-quality evidence):

- Those who required multiple epinephrine doses

- Respiratory failure, end-organ damage, cardiovascular shock or arrest.

In summary, don’t extrapolate too much, but the routine use of steroids is probably not ideal. There are, however, select patients that will still benefit:

- Refractory anaphylaxis

- Cardiovascular shock

- Concurrent asthma with anaphylaxis (clear benefit shown with steroids)

“If I’m going to use a steroid, which one should I use?”

If you choose to use a steroid, a careful agent selection that is ideal for your patient can have a much greater benefit than simply throwing IV methylprednisolone at them.

- Methylprednisolone is associated with the highest rates of steroid-induced anaphylaxis, urticaria, and angioedema of all steroids

- For this reason, consider using dexamethasone vs hydrocortisone, letting the patients presentation guide our choice

- When to consider dexamethasone: Dominant upper/lower respiratory involvement are responsive to this medications anti-inflammatory effects, as well as its longer duration of action.

- When to consider hydrocortisone: If the patient continues to be hypotensive, mineralocorticoid effects from hydrocortisone may play a higher benefit in this shock or shock-like state.

If there’s one take home point from biphasic reactions and steroid use, it’s that the number one medication to prevent relapse and bounce-back from anaphylaxis is epinephrine.